[:it]By Michael Breveglieri

Head of Health and HIV Prevention

There new prevention campaign of Arcigay has sparked much debate. It is a campaign with a specific theme that focuses on awareness of risks and tools with their limitations and potential. Despite the nine themes and actions highlighted, some have provoked inappropriate and selective reactions, ignoring the campaign's overall approach.

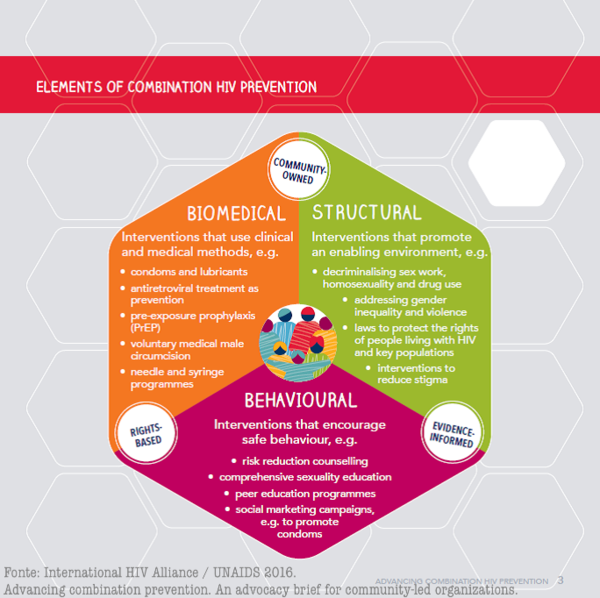

The Ministry of Health, thanks to the L and M sections of the Technical-Health Committee (of which Arcigay is also a part), has just released a National Plan to Fight AIDS, signed by the Regions less than a month ago, which sets out the guidelines for achieving UNAIDS's crucial global goal of ending AIDS by 2030. The ministerial policy document says: “The complex nature of the epidemic implies the need for combined prevention programs, which take into account factors specific to each context, and which also include programs to reduce stigma and discrimination. (…) Combined programs can be implemented at the individual, community and general population levels and must be based on evidence regarding the progress of the epidemic”. The combined intervention implies, among other things and in addition to condoms, also “pharmacological interventions: prevention strategies based on the use of antiretroviral drugs (PrEP, PEP, TasP)”. On MSM (men who have sex with men), in particular and among other things: “Promote a targeted “combined prevention” approach that includes PrEP, TasP and PEP, community-based programs offering rapid HIV and STI tests, vaccinations for MSM in frequented places, according to current guidelines”. All this plus the condom.

It's curious that those waging war on an effective strategy to stop HIV today are not the institutions, historically absent in Italy, but sections of the community and self-proclaimed prevention experts. Curious because we should all be working instead to achieve the actual implementation of this strategy, which our country is dramatically behind on, but which is proving to be the only effective way to contain the epidemic. But we'll return to this curious paradox at the end.

The condom is the most versatile and useful tool of all: we say it, but without hiding the reality.

We've always said that condoms are the most versatile and useful tool of all, and we're saying it again with this campaign. Explicitly. It's the only one that protects against HIV and many other sexually transmitted infections during penetrative sex (though not necessarily contact infections, like HPV). It's the only one that can be used to protect against oral sex, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, and even, if you're committed, against hepatitis A (if you use it as a barrier, cut like a sheet, between your mouth and anus). The condom used correctly and always, with only the residual risk of breakage, It has an estimated protection of around 99.5%.

We've always said that condoms are the most versatile and useful tool of all, and we're saying it again with this campaign. Explicitly. It's the only one that protects against HIV and many other sexually transmitted infections during penetrative sex (though not necessarily contact infections, like HPV). It's the only one that can be used to protect against oral sex, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, and even, if you're committed, against hepatitis A (if you use it as a barrier, cut like a sheet, between your mouth and anus). The condom used correctly and always, with only the residual risk of breakage, It has an estimated protection of around 99.5%.

But on our part we believe it is more responsible to face reality, that is, there's a large community that doesn't consistently use condoms, and that endlessly reiterating a rule won't change the situation. It will change it for some, but not significantly for many. If that weren't the case, we would have seen a drastic decline in the epidemic long ago. But that's not the case. On the contrary.

For many people, condoms are easy to use. It's not a problem. And many use them all the time, at least in casual sex. It's a good thing they continue to do so., because it's the best tool in terms of broad-spectrum effectiveness. We even say so in the campaign and distribute it in bulk. But you should know that the benefit you get from it is strictly related to this "consistency." And we say this too. Using it only sometimes and not always, becomes a problem even in terms of subjective perception of risk: thinking you're "okay" just because you use it "almost always". The EMIS study in 2010 of more than 16,800 MSM in Italy told us that among those who had had sex with casual partners in the last year, 40.4% had not used a condom for anal sex at least once with casual partners. The 60% was therefore intended for constant use. But what about the others?

The problem is that Individual risk management does not take place in a theoretical or laboratory context, but in a practical, real-life context where adherence to “technique” is everything. (because we are always talking about medicalized techniques, whether it is a mechanical barrier such as the condom or pharmacological means such as PrEP and TasP). Adherence to the condom always and in any case is unfortunately only theoretical and the social norm on its use is so strong that it is difficult even to estimate its real "violation", as can be read in This CDC (Center for Disease Control) page on comparing risk reduction strategies in anal sex among MSM. CDC reports a study published in 2015 who analyzed data from the EXPLORE and VAX004 studies, estimating the effectiveness of condoms in real life in a subgroup of people who reported consistent condom use during anal sex at 100%: effectiveness of 70% compared to complete non-use (you can also see a discussion here). That is, there were infections in that subgroup too.

Certainly this result cannot be due to the condom itself, which we reiterate has an efficacy beyond that of 99% in laboratory conditions, but is probably due to the fact that some may have declared constant use for mere “social desirability”, that is, to please the “social norm” on condom use in front of the researchers. But if even in a study a person fails to recognize their own inconstancy and therefore their degree of risk, and ends up complying with a norm only "in words", what should we think of real life? This explains why the condom contained the epidemic, but did not stop it.

Not only that. On the one hand, the analysis of the above-mentioned studies shows no statistically significant difference between "sometimes" use and no use with respect to risk outcomes. On the other hand, it shows that the strategy faces difficulties in the long term: over three years, only 13% of participants reported constant use of 100% for anal sex, while 95.5% reported having used it at least once. Inconstancy is therefore the most constant behavior. You can find a discussion on the topic here.

It is therefore incorrect to take on the responsibility of proposing a possible alternative to at least a part of that 40,4% of MSM identified by the EMIS study in 2010? We don't think so. There are those who prefer to continue to butt heads with reality by reiterating abstract principles. We don't. For us, reality demands concrete and realistic answers.

If you want to familiarize yourself with the topic of risk reduction and you know English, you can use this interesting risk assessment tool, from the CDC: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/hivrisk/estimator.html

The fear of TasP, or the fear of being HIV positive “regardless”.

Before we get to PrEP, let's talk about TasP (therapy as prevention). This is the strategy based on the fact that a person with HIV who follows consistent therapy and has "undetectable" virus levels in their blood or below 200 copies does not transmit the virus. In the same way, CDC page cited above, let's look at the 2011 data from the HPTN 052 study which spoke of a reduction in 96%. But then, with the continuation of that same study and with other studies, TasP demonstrated virtually complete efficacy. Zero risk. Two studies have confirmed this, “Opposites Attract” And "“Partner”, the latest results of which came between 2016 and 2017. Between the two studies, out of over 40,000 sexual intercourses without a condom in HIV-discordant gay couples (one HIV positive, the other HIV negative) there were ZERO infections From the HIV-infected partner. There have been infections, but phylogenetically they did not originate from the partner (they came from outside the couple). The presence of other STIs in the couple did not change anything.

Before we get to PrEP, let's talk about TasP (therapy as prevention). This is the strategy based on the fact that a person with HIV who follows consistent therapy and has "undetectable" virus levels in their blood or below 200 copies does not transmit the virus. In the same way, CDC page cited above, let's look at the 2011 data from the HPTN 052 study which spoke of a reduction in 96%. But then, with the continuation of that same study and with other studies, TasP demonstrated virtually complete efficacy. Zero risk. Two studies have confirmed this, “Opposites Attract” And "“Partner”, the latest results of which came between 2016 and 2017. Between the two studies, out of over 40,000 sexual intercourses without a condom in HIV-discordant gay couples (one HIV positive, the other HIV negative) there were ZERO infections From the HIV-infected partner. There have been infections, but phylogenetically they did not originate from the partner (they came from outside the couple). The presence of other STIs in the couple did not change anything.

The objections to the TasP are truly astonishing. It's clear that not using condoms in a HIV-discordant couple leaves the issue of STIs open (if the couple is not monogamous), just as it's obviously clear that one can't lightly engage in casual sex with an HIV-positive partner "on trust," because one can't control the person's actual clinical status. In fact, that's not what we're saying, not even in the campaign. But Why not consider it a natural option for a couple supposedly built on dialogue and sharing, if they feel the need not to use condoms? In the "Opposites Attracts" study, undetectable status remained a constant in 98% cases, which is not surprising given the dual motivational value of having a guaranteed long life and not even being infectious thanks to treatment for HIV-positive individuals. Viremia is routinely monitored at least every six months. The objection about the possible difference in viral load between blood and semen is misplaced: There are deviations, but in addition to the fact that they are not particularly significant, the two aforementioned studies found ZERO infections with a blood viremia below 200 copies. Whether there were more or fewer copies in the sperm, the result is still ZERO.

On September 27, 2017 CDC, which is notoriously an institution with a conservative approach on these issues, he officially said: “when antiretroviral therapy results in viral suppression, defined as less than 200 copies/ml or undetectable, it prevents sexual transmission of HIV. (…) This means that People who take therapy daily as prescribed and who achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load have effectively no risk of sexually transmitting the virus to an HIV-negative partner.”.

The portrayal of a person with HIV as potentially dangerous "no matter what" speaks much more to the need to maintain an irrational fear and maintain a reassuring distance between oneself and the HIV-positive person than to the desire to take action to prevent it. The fear is legitimate, but it remains irrational. And it's even worse for those who "have lots of HIV-positive friends.".

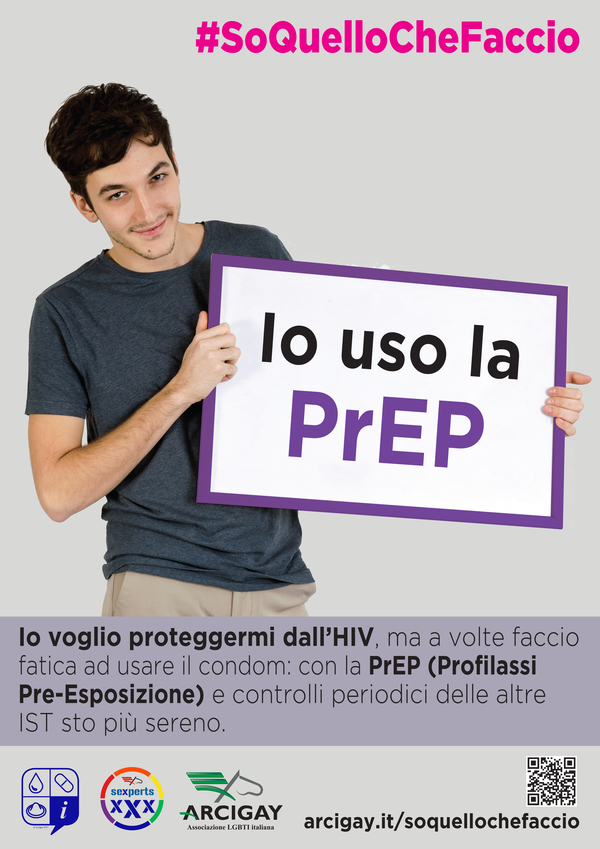

PrEP is undeniably effective for HIV. And adherence is everything, like with condoms.

PrEP, as we also wrote on the campaign page, must be taken with a medical prescription and after having done some initial tests: A kidney checkup, for example, is mandatory, as is an HIV test. The infectious disease specialist is well-equipped to assess the actual need for PrEP, explain the side effects to the person, prescribe the necessary tests and the dosage required for effective PrEP. The person on PrEP will then have periodic check-ups To ensure that everything is fine with regard to her health and any side effects. These checks, in accordance with the Italian guidelines that are about to be finalized, also include checks for other STIs.

PrEP, as we also wrote on the campaign page, must be taken with a medical prescription and after having done some initial tests: A kidney checkup, for example, is mandatory, as is an HIV test. The infectious disease specialist is well-equipped to assess the actual need for PrEP, explain the side effects to the person, prescribe the necessary tests and the dosage required for effective PrEP. The person on PrEP will then have periodic check-ups To ensure that everything is fine with regard to her health and any side effects. These checks, in accordance with the Italian guidelines that are about to be finalized, also include checks for other STIs.

This is the advice we give about PrEP on our campaign page, also reiterating that PrEP only protects against HIV and NOT against other STIs (so much so that we recommend periodic checks). But while we are busy closing the barn by postponing correct procedures for his hiring, the horse has already bolted. MSM are already taking PrEP without a prescription, unaccompanied, and online, even though it's illegal or borderline legal. The stigma surrounding PrEP and the lack of regulated access are already producing what the French called a few years ago (before introducing regulation) "PrEP sauvage," or wild PrEP.

After that, correct and prescribed use of PrEP protects up to 99%. Always starting from the CDC page, there is talk of a protection of 92% according to the iPrEX study published in 2010, percentage relative to those subjects who at least had the drug in their blood (regardless of the quantity). But subsequent analyses have shown that protection can reach 99% with drug levels of daily adherence. In iPrEX OLE, among those using PrEP with a blood concentration compatible with 4-7 pills per week no infection occurred (you see here is the video (of the presentation at the 2014 World AIDS Conference). A summary of iPrEX and iPrEX Ole can be found here. Finally, at CROI 2015 the data were presented HYPERGAY and of PROUD: both studies showed protection average of the 86%. Protection average This means that yes, there were some infections in the two groups studied, but in both Ipergay and Proud the only participants who became infected had actually stopped using PrEP. In terms of community effectiveness, where PrEP is already a prevention tool, we are seeing significant drops in new HIV infections among MSM. PrEP, when used correctly and when effective, is another weapon we have in the fight against the spread of the HIV epidemic.

For MSM it works particularly well also because it has a better performance in anal sex (the drug concentrates more in those tissues): This is one of the reasons why MSM are a prime target for this strategy. However, it's clear that, even for PrEP, adherence is crucial. At least four pills a week are needed for adequate protection in MSM.

The popular argument that a person who doesn't consistently use a condom wouldn't consistently use PrEP is weak., because the two situations and their subjective experiences are incomparable. Interrupting the moment of sex and erotic passion to use a barrier and taking a routine pill at a completely different time from sex are two incomparable situations and can only be subjectively assessed as more or less easy. Likewise, the objection that PrEP is dangerous because “one cannot know whether the other is actually using PrEP or not” is also poorly posed: In fact, no one ever said that you can rely on what others say about themselves, especially in casual relationships. In general, prevention methods are chosen for yourself. "I" use PrEP. and then I am protected from HIV, Not The other one uses PrEP, so I'm protected. These are two different messages, and the second one isn't ours, just like we say it makes no sense to ask "are you healthy?" in a casual relationship.

As for side effects, most people do not experience side effects, but some have been reported in clinical studies (comments can be found on the pages linked above). In the Proud study, 13 out of over 500 people discontinued the study due to side effects: 2 for increased creatinine (hence kidney problems), 5 for nausea or diarrhea, 2 for joint pain, and 2 for headaches. All but 2, however, subsequently restarted PrEP use without further problems. In iPrEX, the only significant differences were nausea, headache, or weight loss, again in a minority of the sample, always lower than 5%, which disappeared after a month. 0.3%, on the other hand, had a slight increase in creatinine (hence kidney problems), which, however, regressed as soon as PrEP was stopped. Four out of five who had experienced this effect no longer experienced it after resuming PrEP. When talking about side effects, it must also be considered that PrEP is certainly more effective the more it is taken in adequate doses, but this does not necessarily mean that its use is actually so constant over the course of a lifetime and therefore the long-term cumulative side effects: maybe because you take a break from using a condom, or because you enter into a stable relationship, or for a thousand other reasons why you end it. The dosage tested with the Ipergay study, moreover, also allows us to make our own evaluations regarding a more intermittent and "as needed" use, which has proven to be equally effective if done right.

Combined prevention as a model for the control of HIV and other STIs

It makes no sense for a person who truly always uses condoms without problems to also take PrEP: such a message, paradoxically, would fuel the idea that condoms do not protect. It's somewhat reminiscent of the anxious use of double condoms. It's clear that those who will take PrEP will have the hardest time maintaining condom use or those who tend not to use them at all. It's recommended precisely for these people, so it can become a complementary or alternative tool. Taking a reality check, we acknowledge that some people already need a temporary or permanent alternative tool. Therefore, complementarity, in this case, always refers to the ability of PrEP to replace condoms when there is no condom.

It makes no sense for a person who truly always uses condoms without problems to also take PrEP: such a message, paradoxically, would fuel the idea that condoms do not protect. It's somewhat reminiscent of the anxious use of double condoms. It's clear that those who will take PrEP will have the hardest time maintaining condom use or those who tend not to use them at all. It's recommended precisely for these people, so it can become a complementary or alternative tool. Taking a reality check, we acknowledge that some people already need a temporary or permanent alternative tool. Therefore, complementarity, in this case, always refers to the ability of PrEP to replace condoms when there is no condom.

So much so that in all PrEP guidelines, the key elements for accessing it are inconsistent condom use, having had an STI (sexually transmitted infection) recently, or having used PEP recently. In its campaign, Arcigay simply said what's commonly said: "Having trouble using condoms and not using them consistently? Consider using PrEP.".

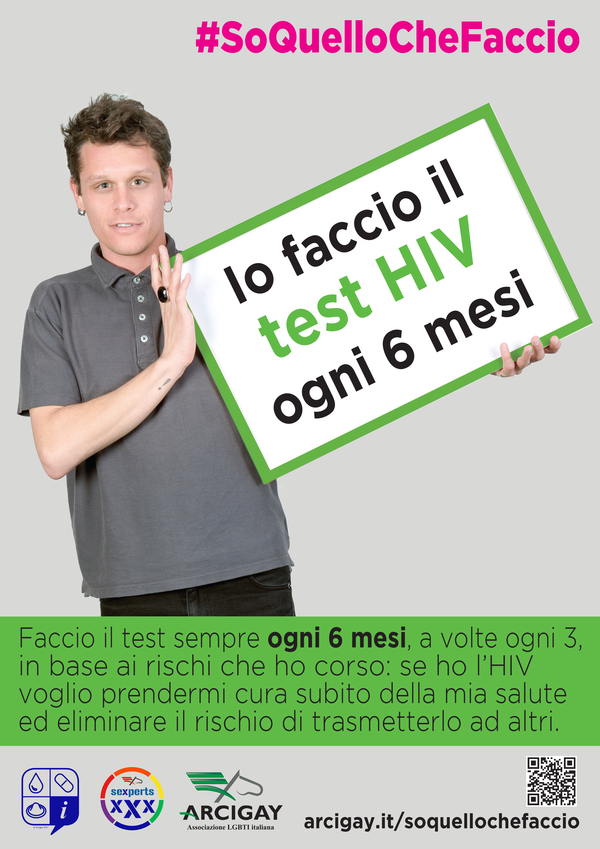

Will there then be an increase in other STIs due to less condom-protected sexual behavior? In reality, this has not been observed in the studies cited. However, in several contexts where PrEP has been in vogue for years (especially in the USA), a decrease in HIV diagnoses has been observed alongside an increase in other STIs, all of which are curable. Is this due to increased testing or the abandonment of condoms? It's unclear. But this It is also the reason why countermeasures have begun to be taken which are proving to have concrete effects on the STI epidemic as well, contrary to expectations. Paradoxically, a careful and truly “combined” strategy around the use of PrEP can also lead to a reduction in other STIs: because the checks and care of the latter are constant.

The English have demonstrated this, with the concrete results of the combination Test+TasP+PrEP+condom being extraordinary. and should be an inspiration to everyone. Not just in some areas of London They are curbing the HIV epidemic among MSM with a decline of 29% never observed in the history of the epidemic, not only is the strategy working across the country with a 18% reduction in new infections across the population (21% in MSM), but in the main and most organised clinic in London they have also observed a decrease in gonorrhoea diagnoses since MSM started using PrEP. The HIV result is explained for the strong and decisive combined prevention strategy which has been put into action in the UK and especially in London where the strategy has been massive: HIV tests almost quadrupled among MSM (about 37,224 in 2007 versus 143,560 in 2016), tests repeatedly offered to those with a more active and risky sexual life, therapy at diagnosis to reduce viremia and essentially put all those diagnosed with HIV on TasP, and finally distribution of condoms and access to PrEP. But according to the researchers the drop in gonorrhea diagnoses in London's most organised clinic It can probably be explained instead by another fact, paradoxically linked to PrEP: those who use PrEP also undergo periodic STI checks (at least every 6 months), and if they are found to be infected, they are treated immediately. This breaks the epidemic chains with unparalleled effectiveness: without the controls induced by PrEP adherence programs, these chains would continue for years.

The English have demonstrated this, with the concrete results of the combination Test+TasP+PrEP+condom being extraordinary. and should be an inspiration to everyone. Not just in some areas of London They are curbing the HIV epidemic among MSM with a decline of 29% never observed in the history of the epidemic, not only is the strategy working across the country with a 18% reduction in new infections across the population (21% in MSM), but in the main and most organised clinic in London they have also observed a decrease in gonorrhoea diagnoses since MSM started using PrEP. The HIV result is explained for the strong and decisive combined prevention strategy which has been put into action in the UK and especially in London where the strategy has been massive: HIV tests almost quadrupled among MSM (about 37,224 in 2007 versus 143,560 in 2016), tests repeatedly offered to those with a more active and risky sexual life, therapy at diagnosis to reduce viremia and essentially put all those diagnosed with HIV on TasP, and finally distribution of condoms and access to PrEP. But according to the researchers the drop in gonorrhea diagnoses in London's most organised clinic It can probably be explained instead by another fact, paradoxically linked to PrEP: those who use PrEP also undergo periodic STI checks (at least every 6 months), and if they are found to be infected, they are treated immediately. This breaks the epidemic chains with unparalleled effectiveness: without the controls induced by PrEP adherence programs, these chains would continue for years.

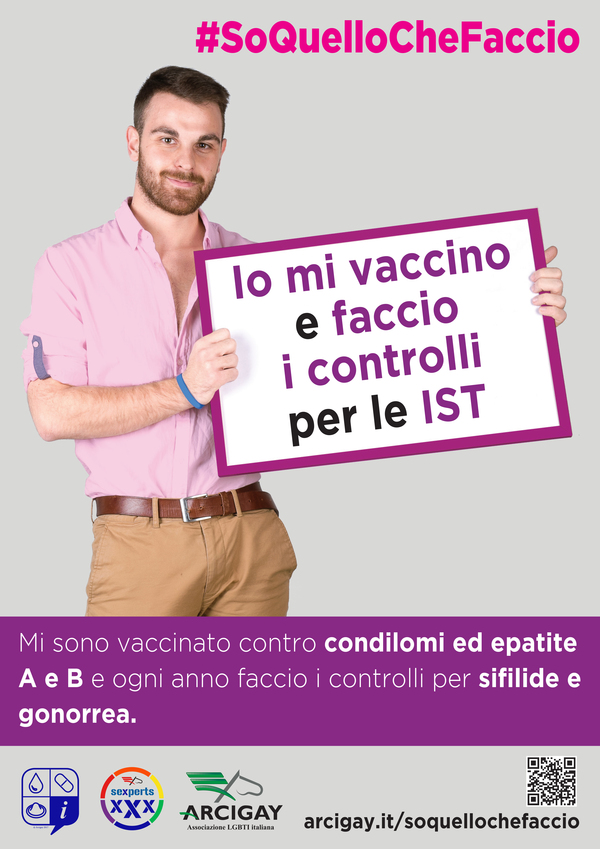

In a context like Italy's, which lacks a comprehensive sexual health approach, this factor is even more relevant: in many areas, getting a free syphilis or gonorrhea test is difficult, resulting in epidemic chains spreading unchecked. This is why this aspect must also be implemented in Italy. For this reason, one of the subjects of Arcigay's campaign is also periodic checks for other STIs and vaccinations where possible.

CDC has recently taken this very position, also following a study based on a mathematical model according to which Taking PrEP, if accompanied by check-ups every 6 months or every 3 months (as per the intake protocol which would also take place in Italy), would lead to a reduction in gonorrhea and syphilis (see also discussion here).

Prevention is not the police force of sex

After examining the merits of the disputed messages, it is a good idea to make a thorough assessment. Because in this debate there is not only a discussion on prevention tools, but a diversity of cultural approaches at the bottom. For Arcigay, prevention is a pragmatic intervention on concrete reality with specific tools that provide answers to that reality, and it is also an intervention on individual and community awareness while respecting the self-determination of the person. For others, however, prevention is an imperative that we can easily define as moral and normative., is an abstract principle that must be reaffirmed idealistically regardless. The tools of prevention, for this second approach, are ideal and normative simulacra. It doesn't matter whether or not there's an effective grasp of reality behind them. What's important is to reaffirm them regardless.

We know how our community got to this point, but it's appropriate to talk about it. The spread and entrenchment of a normative expectation about good sex, that is, the proper use of condoms to identify not only a prevention practice, but also a "good, right and intelligent" sex and indirectly the person who does it, saved many lives. Until 1995 there was only one way to avoid getting infected and, at that time, dying: use a condom, or abstain, or be monogamous. In a community accustomed to experiencing sex joyfully, and which had made sexual liberation its driving force until the advent of AIDS, the use of condoms was the acceptable normative compromise and the only effective means of saving one's life. Faced with a massacre, getting people to mutually control the use of a barrier (that's what it's technically called) was the last resort for a community's survival. Then, from 1995 onwards, highly effective antiretroviral drugs arrived, AIDS cases dropped but not HIV infections, and the debate began on the unwanted effects of "salvation": that is, the archiving of fear. and if it were counterproductive to say that "we don't die anymore". Beyond the fact that then as now people still die (but for different reasons and in much smaller numbers due mostly to the irreparable delay in diagnosis, also due to the fear of the test), the point is that for many commentators on the historic change introduced by medicine in 1995 fear had to remain the necessary and indispensable element of prevention. With a contradiction that is latent and increasingly problematic to manage over the years: How can you tell someone to take the test with peace of mind if you've instilled in them the seed of fear of the result and that fear is functional to your prevention talk? It's no coincidence that, especially since 2000, the main prevention issues have been two: how do we tell people to get tested if we scare them, and how do we make them embrace a barrier like the condom? Stigma towards people with HIV was not even on the agenda for many years. In 2008, the Swiss statement on TasP arrived, the first ever. There was horror and fear even in the medical-scientific community over the "dangerousness" of claiming that a person with HIV and an undetectable viral load cannot transmit the virus. History and studies later proved the Swiss right, and the medical-scientific community realigned itself. But, paradoxically, it seems that part of the gay community itself remains "appalled.". Then came PrEP, and in 2012 in the USA the term “Truvada Whores” was even coined to stigmatize people who irresponsibly persist in breaking a community legal code on sex, and they do so knowingly by seeking alternatives to have "the sex they want.".

Praise of fear, attribution of stigma and shame are the cultural alchemical elements that we see returning today in various commentaries and various forms. Behind this lies the fear, even a collective one, that a mutually and widely recognized norm, which acted as a barrier to death in the dark ages, will collapse. It matters little that the combined broadening of perspective and tools is now more effective in controlling the epidemic, and that the data incontrovertibly demonstrate that condoms have contained the epidemic, but not stopped it, because the reality of epidemic dynamics is a little more complicated than repeating a rule. It matters little that reality is something different from the story that is told about it. must Do. Prevention is and must remain a regulatory issue, a "must be" of "good and just sex," and it cannot be left to the informed awareness and self-determination of individuals. The means has become the end. Regardless. Even subjective “pleasure” has become either irrelevant in the prevention debate (“it doesn’t matter whether you like it or not, you have to do this”), stigmatized if subjectively experienced without a condom (the debate on “Truvada whores” teaches us this), or finally a normative element in itself (you can’t not like it even with a condom).

Praise of fear, attribution of stigma and shame are the cultural alchemical elements that we see returning today in various commentaries and various forms. Behind this lies the fear, even a collective one, that a mutually and widely recognized norm, which acted as a barrier to death in the dark ages, will collapse. It matters little that the combined broadening of perspective and tools is now more effective in controlling the epidemic, and that the data incontrovertibly demonstrate that condoms have contained the epidemic, but not stopped it, because the reality of epidemic dynamics is a little more complicated than repeating a rule. It matters little that reality is something different from the story that is told about it. must Do. Prevention is and must remain a regulatory issue, a "must be" of "good and just sex," and it cannot be left to the informed awareness and self-determination of individuals. The means has become the end. Regardless. Even subjective “pleasure” has become either irrelevant in the prevention debate (“it doesn’t matter whether you like it or not, you have to do this”), stigmatized if subjectively experienced without a condom (the debate on “Truvada whores” teaches us this), or finally a normative element in itself (you can’t not like it even with a condom).

Yet even for the WHO, sexual health is no longer just a matter of the absence of disease in sex. It's also a question of overall well-being in sex and the pursuit of pleasure, which also includes the tools to avoid disease. The tools must serve well-being, not the other way around.

Escaping a thirty-year narrative of fear that has itself produced so much stigma is not easy. But we live in a historical moment in which resources have increased and we know much more about the epidemic, about HIV first and foremost, but also about other STIs. Engaging in a narrative of awareness about all the risks and all the means available to one's needs, starting with the condom as the most versatile means, but without hiding anything, is even more challenging. Many of us, most of us, are perfectly fine without PrEP and using condoms, and prefer not to risk syphilis and the painful bites it requires to treat it. But we're not all the same. We acknowledge that. [:]